2. Machine Model#

After reading this chapter you will understand the abstract model of a parallel computing node which underlies the design choices and structure of the Kokkos framework. The machine model ensures the applications written using Kokkos will have portability across architectures while being performant on a range of hardware.

The machine model has two important components:

Memory spaces, in which data structures can be allocated

Execution spaces, which execute parallel operations using data from one or more memory spaces.

2.1 Motivations#

Kokkos is comprised of two orthogonal aspects. The first of these is an underlying abstract machine model which describes fundamental concepts required for the development of future portable and performant high performance computing applications; the second is a concrete instantiation of the programming model written in C++, which allows programmers to write to the concept machine model. It is important to treat these two aspects of Kokkos as distinct entities because the underlying model being used by Kokkos could, in the future, be instantiated in additional languages beyond C++ yet the algorithmic specification would remain valid.

2.1.1 Kokkos Abstract Machine Model#

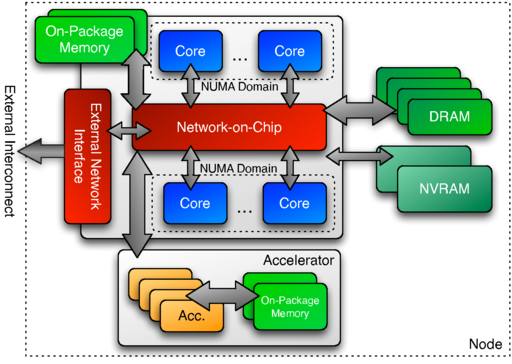

Kokkos assumes an abstract machine model for the design of future shared-memory computing architectures. The model (shown in Figure 2.1) assumes that there may be multiple execution units in a compute node. For a more general discussion of abstract machine models for Exascale computing the reader should consult reference Ang1. In the figure shown here, we have elected to show two different types of compute units - one which represents multiple latency-optimized cores, similar to contemporary processor cores, and a second source of compute in the form of an off die accelerator. Of note is that the processor and accelerator each have distinct memories, each with unique performance properties, that may or may not be accessible across the node (i.e. the memory may be reachable or shared by all execution units, but specific memory spaces may also be only accessible by specific execution units). The specific layout shown in Figure 2.1 is an instantiation of the Kokkos abstract machine model used to describe the potential for multiple types of compute engines and memories within a single node. In future systems, there may be a range of execution engines which are used in the node ranging from a single type of core, as in many/multicore processors found today, through to a range of execution units where many-core processors may be joined to numerous types of accelerator cores. In order to ensure portability to the potential range of nodes, an abstraction of the compute engines and available memories are required.

1 Ang, J.A., et. al., Abstract Machine Models and Proxy Architectures for Exascale Computing, 2014, Sandia National Laboratories and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, DOE Computer Architecture Laboratories Project

Figure 2.1 Conceptual Model of a Future High Performance Computing Node#

2.2 Kokkos Spaces#

Kokkos uses the term execution spaces to describe a logical grouping of computation units which share an identical set of performance properties. An execution space provides a set of parallel execution resources which can be utilized by the programmer using several types of fundamental parallel operation. For a list of the operations available see Chapter 7 - Parallel dispatch. The term memory spaces is used to describe a logical distinct memory resource, which is available to allocate data.

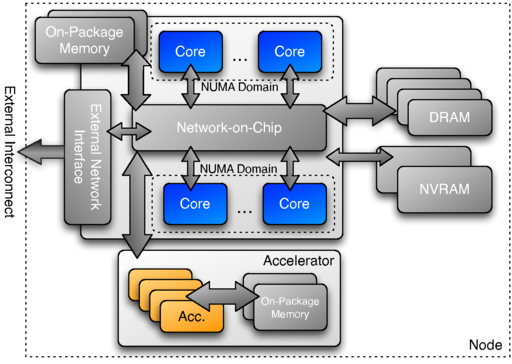

2.2.1 Execution Space Instances#

An instance of an execution space is a specific instantiation of an execution space to which a programmer can target parallel work. By means of example, an execution space might be used to describe a multicore processor. In this example, the execution space contains several homogeneous cores which share some logical grouping. In a program written to the Kokkos model, an instance of this execution space would be made available on which parallel kernels could be executed. As a second example, if we were to add a GPU to the multicore processor so a second execution space type is available in the system, the application programmer would then have two execution space instances available to select from. The important consideration here is that the method of compiling code for different execution spaces and the dispatch of kernels to instances is abstracted by the Kokkos model. This allows application programmers to be free from writing algorithms in hardware specific languages.

Figure 2.2 Example Execution Spaces in a Future Computing Node#

2.2.2 Kokkos Memory Spaces#

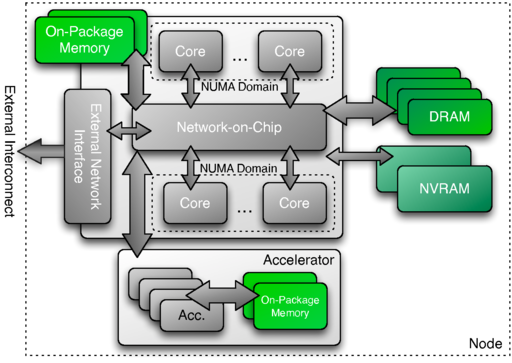

The multiple types of memory which will become available in future computing nodes are abstracted by Kokkos through memory spaces. Each memory space provides a finite storage capacity at which data structures can be allocated and accessed. Different memory space types have different characteristics with respect to accessibility from execution spaces as well as their performance characteristics.

2.2.3 Instances of Kokkos Memory Spaces#

In much the same way execution spaces have specific instantiations through the availability of an instance so do memory spaces. An instance of a memory space provides a concrete method for the application programmer to request data storage allocations. Returning to the examples provided for execution spaces, the multicore processor may have multiple memory spaces available including on-package memory, slower DRAM and additional sets of non-volatile memories. The GPU may also provide an additional memory space through its local on-package memory. The programmer is free to decide where each data structure may be allocated by requesting these from the specific instance associated with that memory space. Kokkos provides the appropriate abstraction of the allocation routines and any associated data management operations including releasing the memory, returning it for future use, as well as for copy operations.

Figure 2.3 Example Memory Spaces in a Future Computing Node#

Atomic accesses to Memory in Kokkos In cases where multiple executing threads attempt to read a memory address, complete a computation on the item, and write it back to same address in memory, an ordering collision may occur. These situations, known as race conditions (because the data value stored in memory as the threads complete is dependent on which thread completes its memory operation last), are often the cause of non-determinism in parallel programs. A number of methods can be employed to ensure that race conditions do not occur in parallel programs including the use of locks (which allow only a single thread to gain access to data structure at a time), critical regions (which allow only one thread to execute a code sequence at any point in time) and atomic operations. Memory operations which are atomic guarantee that a read, simple computation, and write to memory are completed as a single unit. This might allow application programmers to safely increment a memory value for instance, or more commonly, to safely accumulate values from multiple threads into a single memory location.

Memory Consistency in Kokkos Memory consistency models are a complex topic in and of themselves and usually rely on complex operations associated with hardware caches or memory access coherency (for more information see Hennessy and Paterson2). Kokkos does not require caches to be present in hardware and so assumes an extremely weak memory consistency model. In the Kokkos model, the programmer should not assume any specific ordering of memory operations being issued by a kernel. This has the potential to create race conditions between memory operations if these are not appropriately protected. In order to provide a guarantee that memory operations are completed, Kokkos provides a fence operation which forces the compute engine to complete all outstanding memory operations before any new ones can be issued. With appropriate use of fences, programmers are thereby able to ensure that guarantees can be made as to when data will definitely have been written to memory.

2 Hennessy J.L. and Paterson D.A., Computer Architecture, Fifth Edition: A Quantitative Approach, Morgan Kaufmann, 2011.

2.3 Program execution#

It is tempting to try to define formally what it means for a processor to execute code. None of us authors have a background in logic or what computer scientists call “formal methods,” so our attempt might not go very far! We will stick with informal definitions and rely on Kokkos’ C++ implementation as an existence proof that the definitions make sense.

Kokkos lets users tell execution spaces to execute parallel operations. These include parallel for, reduce, and scan (see Chapter 7 - Parallel dispatch) as well as View allocation and Initialization. We name the class of all such operations parallel dispatch.

From our perspective, there are three kinds of code:

Code executing inside of a Kokkos parallel operation

Code outside of a Kokkos parallel operation that asks Kokkos to do something (e.g., parallel dispatch itself)

Code that has nothing to do with Kokkos

The first category is the most restrictive. Section 8.2 explains restrictions on inter-team synchronization. In general, we limit the ability of Kokkos-parallel code to invoke Kokkos operations (other than for nested parallelism; see Chapter 8 - Hierarchical Parallelism and especially Section 8.2). We also forbid dynamic memory allocation (other than from the team’s scratch pad) in parallel operations. Whether Kokkos-parallel code may invoke operating system routines or third-party libraries depends on the execution and memory spaces being used. Regardless, restrictions on inter-team synchronization have implications for things like filesystem access.

Kokkos threads are for computing in parallel, not for overlapping I/O and computation, and not for making graphical user interfaces responsive. Use other kinds of threads (e.g., operating system threads) for the latter two purposes. You may be able to mix Kokkos’ parallelism with other kinds of threads; see Section 2.3.1. Kokkos’ developers are also working on a task parallelism model that will work with Kokkos’ existing data-parallel constructs.

Reproducible reductions and scans Kokkos promises nothing about the order in which the iterations of a parallel loop occur. However, it does promise that if you execute the same parallel reduction or scan, using the same hardware resources and run-time settings, then you will get the same results each time you run the operation. “Same results” even means “with respect to floating-point rounding error.”

Asynchronous parallel dispatch This concerns the second category of code that calls Kokkos operations. In Kokkos, parallel dispatch executes asynchronously. This means that it may return “early,” before it has actually completed. Nevertheless, it executes in sequence with respect to other Kokkos operations on the same execution or memory space. This matters for things like timing. For example, a parallel_for() may return “right away,” so if you want to measure how long it takes, you must first call fence() on that execution space. This forces all functors to complete before fence() returns.

2.3.1 Thread safety?#

Users may wonder about “thread safety,” that is, whether multiple operating system threads may safely call into Kokkos concurrently. Kokkos’ thread safety depends on both its implementation and on the execution and memory spaces that the implementation uses. The C++ implementation has made great progress towards (non-Kokkos) thread safety of View memory management. For now, however, the most portable approach is for only one (non-Kokkos) thread of execution to control Kokkos. Also, be aware that operating system threads might interfere with Kokkos’ performance depending on the execution space that you use.